Fall 2024 (September – December)

- Foundations of Human Rights and Social Justice (HRSJ 5010)

- Indigenous Ways of Knowing: Resurgence of Land-Based Pedagogies and Practices (HRSJ 5020)

- Food, Art and Community Empowerment (HRSJ 5710)

In Fall 2024, I did the three courses mentioned above, 2 of which were mandatory, and one (HRSJ 5710) was an elective course.

In the ‘Foundations of Human Rights and Social Justice’, we explored themes related to human rights and social justice, deepening our understanding of social change towards justice and fairness at local, national, and international levels. We also examined various relevant theoretical frameworks, including Universalism, Relativism, Equity, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI), Intersectionality, Distributive Justice, Critical Race Theory, Disability Theory, Feminist Analysis, and the influence of social and political structures, among others. Additionally, we discussed thematic areas involving the practical application of these theories in both international and domestic contexts, such as Human Rights laws, Social Movements and activism, Human Rights procedures, torture, lack of legal processes, standards and remedies, the duty to accommodate, access to justice, disability rights, Aboriginal rights, Decolonisation and Reconciliation, Refugee and Immigrant Rights, intersecting discrimination and oppression, humanitarian intervention, and Peace Education.

Pictures Taken at Kamloops Indian Residential School Tour. On September 25th, 2024.

In ‘Indigenous Ways of Knowing: Resurgence of Land-based Pedagogies and Practices,’ taught by the knowledgeable Dr Jenna Woodrow and supported by Tracy Strain, we examined Indigenous land-based epistemologies within an interdisciplinary framework that includes Indigenous law, geography, social work, education, health, and wellness. Through alignment with Indigenous intergenerational land-based contexts, practices, and processes, we experienced and articulated ethical ways of living that honour Indigenous self-determination and sovereignty. We also investigated how policies and practices of colonialism and violence systematically deny Indigenous access to the land. At the same time, diverse resistance and resurgence movements assert Indigenous rights regarding food, water, education, ceremony, and movement.

Field Trip to Tk’emlups Te Secwepemc Food Sovereignty Garden, on September 24, 2024.

In ‘Food, Art, and Community Empowerment’, Dr Robin Westland and Twyla Exner introduced us to historical and contemporary issues related to human rights and social justice. We learnt about social, economic, political, and environmental challenges using advanced interdisciplinary theoretical and methodological frameworks.

Reflection on Vandana Shiva’s Who Really Feeds the World?

Throughout the Autumn of 2024, we focused on weekly reflections on Vandana Shiva’s book, ‘Who Really Feeds the World?’ as part of the course Food, Arts, and Community Empowerment. This ongoing engagement with the text became a significant part of my learning journey in the Master of Arts programme. During this course, I consistently asked myself an important question: Can we feed the world? I repeated this question often because the readings and discussions made me realise that providing enough and healthy food for a global population of more than eight billion is a major challenge for society, science, and technology.

My perception of food and its significance changed profoundly after completing this course. I now see food not just as something to eat but as an embodied life force. This course has transformed my understanding of the global food system and prompted me to reconsider my relationship with food, my body, and the Earth. I have come to view this relationship as a symbiotic interaction. As a living being, I benefit from Mother Earth’s kindness, who provides the food I consume. Simultaneously, I acknowledge myself as a potential return to the soil, which nurtures and sustains the cycle of life enabling food to exist.

Vandana Shiva’s critical examination of industrial agriculture and her defence of small-scale, traditional farming practices also drew my attention to the political dimensions of food. Questions about who gets to eat, what they eat, how often, and by what means are deeply politicised issues. Shiva insists that “Small-scale farmers feed the world, not large-scale industrial farms.” This claim challenged me to think critically about dominant narratives in global food production. Yet, it also left me reflecting on whether small-scale farming practices, with their diversity and resilience, can withstand the immense pressures and ambitions of the modern biotechnology industry.

This assignment was meaningful to me because it compelled me to look beyond viewing food as merely a matter of personal consumption and nutrition. It encouraged me to regard food as a deeply interconnected issue—touching on politics, ecology, economics, and culture. Most importantly, it awakened in me a new sense of responsibility regarding how I think about food, the systems that produce it, and the importance of supporting sustainable practices that honour both people and the planet.

Free link to book, provided by Azade: https://www.are.na/block/3845653

Field Trip to the Stir, Butler Urban Farm on October 8, 2024.

Picture Taken After our Final Project Sharing Celebration on November 26, 2024.

Winter 2025 (January – April)

- Problem Solving in the Field: Study Techniques and Methods (HRSJ 5030)

- Settler Colonialism: Decolonization and Responsibility (HRSJ 5120)

- Moral Economies and Social Movements in Contemporary Capitalism (5260)

In the Winter of 2025, I took three courses, one of which was a mandatory course (HRSJ 5030), while the other two were electives.

In the ‘Problem Solving in the Field: Study Techniques and Methods’, we examined social science and humanities field research as multidisciplinary practices that occur across a range of contexts and locations. We engaged with qualitative epistemologies, research choices, and ethical considerations. We also explored Indigenous and anti-colonial approaches to research methods, including data collection and analysis conducted in the global south. Additionally, we learnt to develop a comprehensive research proposal and consider its ethical implications.

In the ‘Moral Economies and Social Movements in Contemporary Capitalism’, Dr Terry Kading and Dr Alana Toulin, drawing on geography, sociology, anthropology, and law, examined contemporary capitalism as a system connecting extraction, production, consumption, and disposal at different spatial scales and across political jurisdictions, as well as diverse cultural and social contexts. The course began with the moral economists’ critique of capitalism and its redefinition of human relations; thereafter, we examined economic globalization under deregulated capitalism. Furthermore, we explored moral economies in terms of production, labour, commodification, valuation, and movements that resist capitalist extraction and exploitation, including labour, migrant, environmental, and gender justice movements.

In ‘Settler Colonialism: Decolonization and Responsibility’, Dr Lisa Cooke and Dr Robin Westland revealed and taught us how settler colonialism functions as a distinct ongoing structure rather than just a historical event. They emphasized during the lesson how settler colonialism is studied as a cultural project of open colonial domination, creating new nations such as Canada, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand. According to them, settler colonialism is based on the continuous dispossession of Indigenous Peoples from their land. We also explored how settler colonialism arose from colonial expansion and domination worldwide, and how it manifests and sustains itself locally. Additionally, we reflected on our own relationship to settler colonization. We discussed ways it can be unsettled through weekly reflections on Arthur Manuel and Grand Chief Ronald M. Derrickson’s book titled ‘Unsettling Canada: A National Wake-up Call.’

Summer 2025 (May – August)

- Human Rights and Social Justice Field Experience (HRSJ 5040)

- Master of Arts E-Portfolio (HRSJ 5940)

In the summer of 2025, I completed my practicum as an Indigenous and Wellness Support Worker at the Canadian Mental Health Association (Genesis Place) Kamloops Branch. My practicum experience was both transformative and highly educational. (cf. My Reflection in Practicum) For further details, it includes an analysis of my practicum learning journey. I also began my Master of Arts e-portfolio during that summer, which acts as a marker of my overall learning outcomes for this program.

Fall 2025 (September – December)

- Genocide in the 20th Century (HRSJ 5110)

- Risk, Place, and Social Justice in a Turbulent World (HRSJ 5250)

In fall 2025, since a course-based path was my completion path for this program, I was required to take two courses.

In ‘The Genocide in the 20th Century’, we adopted an interdisciplinary approach to the complex issues of genocide, considering philosophical, historical, and literary perspectives. We explored various aspects of the course, including case studies of genocide, the use of language, the role of eugenics and colonialism, ethical and moral considerations, and international efforts to define and tackle different forms of genocide.

In ‘Risk, Place, and Social Justice in a Turbulent World,’ we investigated different types of risks in society and the diverse populations, places, and life experiences linked to these risks. We examined the planning methods and practices aimed at reducing risks, the gaps in knowledge and policy responses, and how the media reports on various risk types. Using a case study approach, we integrated multiple disciplines through diverse readings from sociology, history, politics, and environmental studies, and assessed, from a social justice perspective, the inclusionary and exclusionary practices involved in risk management.

My Mapping Place Assignment

An Outstanding Assignment

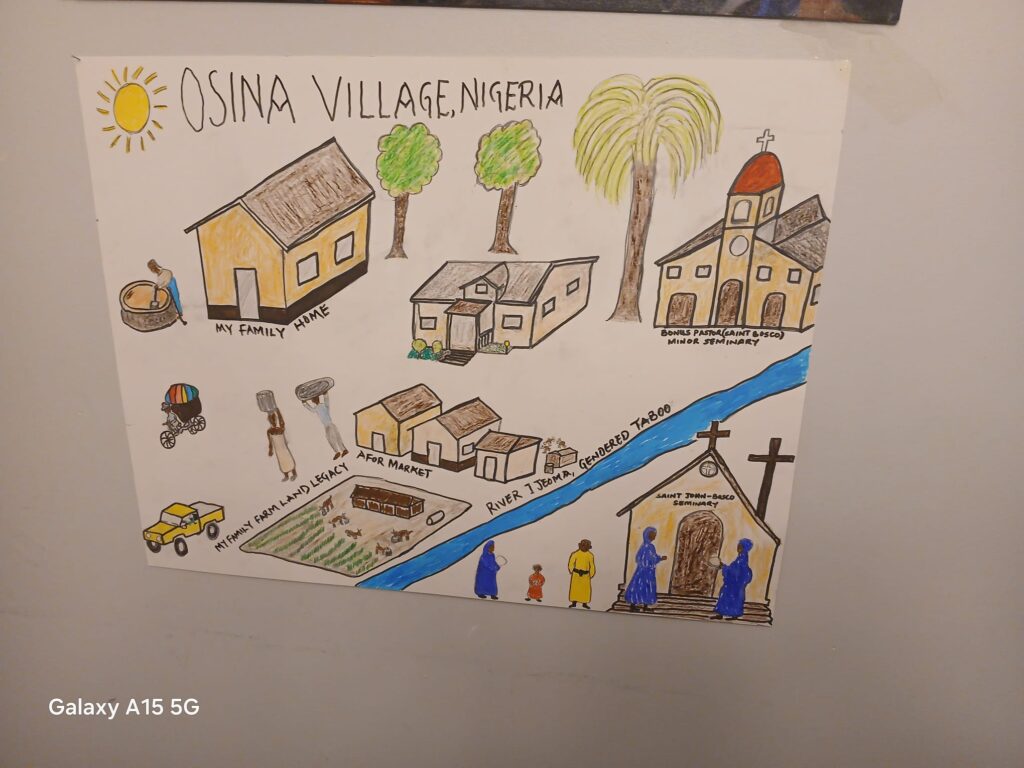

One of the assignments that stood out and had a significant impact during my learning journey in the Master of Arts in Human Rights and Social Justice program was the “Mapping Place” assignment in Settler Colonialism: Decolonization and Responsibilities. For this assignment, we were instructed to create a map of a place that is very important to us, with the purpose of understanding one another through our places in the world and the storyscapes they represent.

In approaching this task, I demonstrated creativity and innovation by deliberately challenging myself to go beyond traditional mapping conventions. Instead of reducing my place to abstract lines and coordinates, I employed a unique method that highlighted the deeper stories, cultural practices, and lived realities embedded in the land. When presenting in class, I delivered my map in an engaging manner that invited my peers to genuinely experience my place—not merely as a physical location, but as a living storyscape woven with memory, culture, and meaning.

This assignment was especially meaningful because it symbolized my family’s strong bond to the land as farmers. My map was more than just a geographical layout; it told a story of identity and belonging. Every aspect of Osina, my cherished village, holds a story—whether it relates to work in the fields, trade at the weekly market, faith in religious institutions, or even cultural restrictions around the Ijeoma River. Through this process, I came to understand that mapping can serve as a form of storytelling and resistance, reclaiming knowledge and highlighting the importance of Indigenous and local ways of knowing.

Ultimately, the “Mapping Place” assignment was meaningful because it helped me realize that places are not just coordinates on a map, but living records of memory, relationships, and responsibilities. It deepened my appreciation for my roots, my family’s farming traditions, and the cultural and intergenerational significance that land holds.